Prey still has the smartest weapon design in games

I don't need a reason, but for an upcoming episode of The Content Mill Podcast (a show where four creators from four corners of the internet talk about what they're making and playing, now available wherever you get your podcasts), I'm doing another run through Arkane's masterpiece, Prey (2017). Prey (I will be dropping the 2017 now that we're all oriented to which one I'm talking about), without a doubt, is my favorite game of all time. But, for today, I don't want to talk about or (re)view Prey. No, I want to talk about a tiny thing Arkane did for their science fiction immersive sim: they made some really silly weapons.

Prey is an immersive sim, a genre that is most easily described as a type of game that responds to player action and allows for player agency in problem-solving. I jokingly say that if you can read an email in a game, it's most likely an immersive sim...and that has mostly held true (casting some real side-eye at Atomic Heart). Immersive sim royalty includes games like System Shock, Thief, Deus Ex, and more recently, the Dishonored games. Each of these games allows players to approach scenarios in multiple different ways, and, generally, the game reacts to those player choices. Prey is a master class in immersive sim game design, allowing players to sneak through vents, repair broken pathways, or go guns blazing through the front door...then reacting to that choice in real time.

But all of that player choice and exploration creates a unique game design problem: how do you facilitate players exploring that space, rather than experiencing it as a linear, flat Call of Duty level? Dishonored has its traversal powers like Blink (a teleport), and Thief has its reactive arrows system, but more science fiction-focused games have struggled to provide the same options as their gaslamp fantasy counterparts. Until Prey, it seemed that the best you could do was some form of box-moving, a Deus Ex mainstay.

Today's post about Prey is about two specific weapons you get very early on and are, in my opinion, genius solutions to the mobility and magic problem a science fiction setting has: the GLOO Cannon and the Huntress Boltcaster.

Let's start with the GLOO Cannon. In universe, the GLOO Cannon is a device built for dealing with environmental hazards. It is a weapon that shoots snowball-sized globs of foam to suppress fires or nullify electrical arcs, but the real utility of the GLOO Cannon is using its foam to encapsulate enemies (allowing for critical hits) or using the globs of GLOO to build platforms for traversal. Instead of needing magical teleport powers like Dishonored, you're able to use GLOO to build ramps to hidden areas above you or mountain goat your way down a steep drop.

Prey is telling you a lot of things in the opening half hour, namely that everything you see is not as it seems, so it shouldn't be surprising that the GLOO Cannon is the first "gun" you receive. The GLOO Cannon and wrench combo is a deadly one-two punch for most enemies, but so is the ability to control the terms of engagement. Sure, you can GLOO that mimic in place for a moment, but what if you simply went over them to find better positioning (or avoid them completely)? By being the first distance weapon you discover, Prey is telling you a few important pieces of information: first, the wrench remains your primary way of dealing with enemies, and, since the wrench requires getting close (and probably getting hurt, since there's no block or dodge), maybe it's best to use this tool to avoid combat.

From the jump, Prey is telling you to question everything, including how you deal with enemies, which is doubly so for the Huntress Boltcaster. The Huntress is a NERF crossbow using foam darts that deal no damage. One of the first times you can encounter the weapon is in an office space with two adjacent desks, separated by cubicle walls. There's a note alluding to one employee using the Huntress to arc the foam darts over the cubicle wall to annoy their roommate. The tutorial text for the weapon also explains that the dart tips react with computer screens.

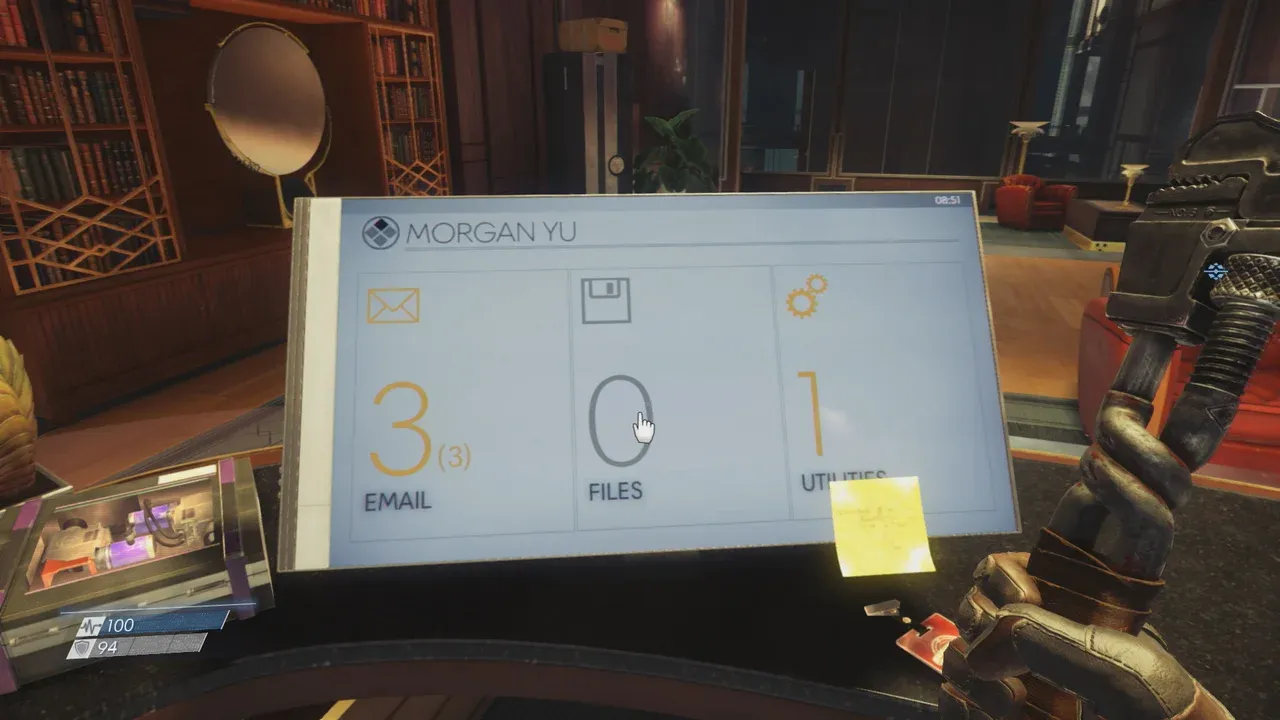

Throughout Prey, you've been interacting with these really large, obnoxious computer screens with three main menus: Emails, Files, and Utilities. The 30+ inch displays are trisected by these menus, a seemingly odd aesthetic choice that only really makes sense once you pick up the Huntress. Emails contain, as you expect, messages between crew members, and the files section usually contains audio logs or schematics for the fabricator. Sometimes it's useful to read messages or download a schematic from afar, but where the Huntress really shines is its ability to trigger utilities: a menu that allows the player to open doors, toggle turrets on or off, or turn on important level distractions.

You can run roughshod through Talos I, clubbing Phantoms and Mimics to death with the wrench you pick up in the game's opening, but it is so much more rewarding to turn on a handful of turrets through an open window and watch, from the safety of the other room, as said turrets do your dirty work on those Phantoms. Heck, if the door is broken open, use your trusty GLOO Cannon to seal it up, then trigger the turrets.

Prey allows players to meet the level on their own terms, rewarding crawling through the vents as much as gathering the proper keycards and walking through the front door. There are always options, but both the GLOO Cannon and the Huntress make you look at level geometry differently. A second-story gantry is no longer out of reach, and each half-open window presents a moment to feel like the smartest person with a NERF blaster in space. Best yet, depending on how you play through Prey, it's possible that your first three weapons in the game are a wrench, the GLOO Cannon, and the Huntress, or their fantasy equivalents: the sword, the misty step, and the mage hand.

You can spec your character into solving these problems in a ton of different ways, but I love how Prey managed to not only provide the vents, keycards, and box-moving abilities to get where you need, it was built in foundationally: from how the weapons are given to you, to what they do, to the actual environmental design of the computer screens. There are so many little, smart choices the team at Arkane made when creating Prey that I don't have enough room to extol them all (the pistol just starts out silenced?!), but if there's one takeaway, I wish more immersive sims—or games cribbing from the genre—would take a lesson from Prey and let me glob some gloop on the wall and climb it.